Around 1860, John Philipps Emslie painted the east side of Red Lion Square, in particular Nos. 22, 23 and 24. According to Edwin Beresford Chancellor’s edition of The History of the Squares of London, 1907, No. 24 was the Ancient Baronial Court, held under the authority of the Sheriffs of Middlesex. “It is held monthly” (says the Gentleman’s Magazine in 1829) “before the Sheriff or his Deputy. Its power in judgment is as great as that of the present Courts at Westminster. It is more expeditious and less expensive; persons seeking to recover debts may do so to any amount at the trifling expense of only six or seven pounds.” From 1842, the Sheriff’s officer, and later Deputy Sheriff, of Middlesex was a member of the Burchell family. In 1890 the office became Deputy Sheriff of the County of London, still at 24 Red Lion Square, until May 1941 when the premises were destroyed.

Between 1886 and 1903, Charles Booth collated over 450 volumes of interviews, questionnaires, observations and statistical information for what was to become his Inquiry into the Life and Labour of the People in London. In 1889 this information was produced as a map.

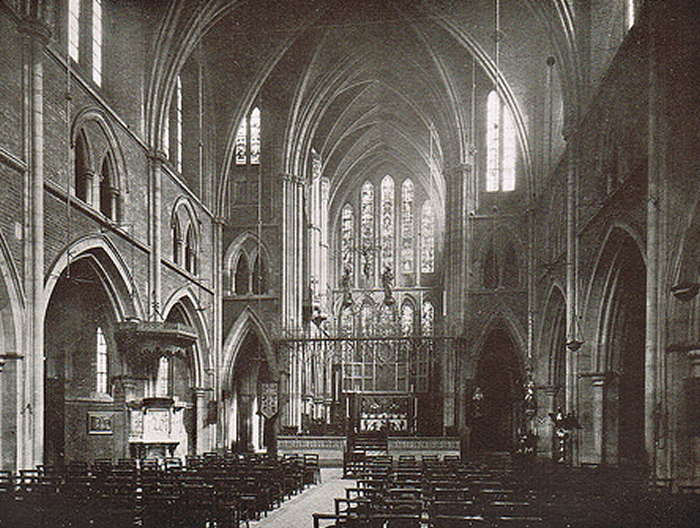

The map uses a spectrum of dark red to dark blue to map from rich to poor, with “Upper-middle and upper classes. Wealthy” picked in orange and “Lowest class. Vicious, semi-criminal” in black. Red Lion Square, at the time occupies the middle ground. Interestingly, Booth’s map also records the arrival of St John the Evangelist church to the west end between Orange Street and Fisher Street. Designed by John L. Pearson, the church was started in 1874 and completed in 1879.

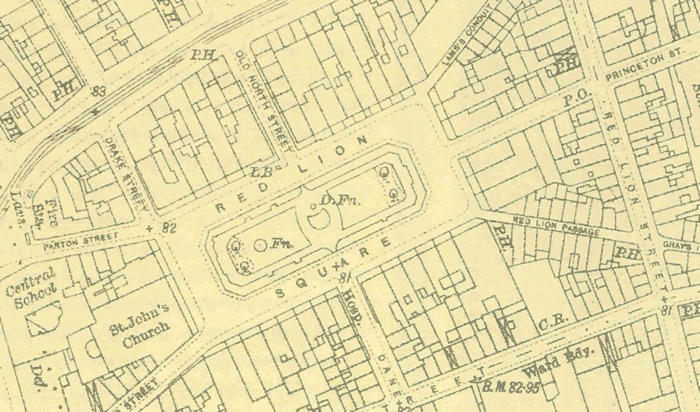

In 1885, the Metropolitan Public Gardens Association planted a garden in the Square, designed by Fanny Wilkinson, the first professional female landscape designer in Britain, which was made open to the general public. Prof. T. C. Barker makes the argument that “the switch from domestic/office/commercial use to commercial/office use” was encouraged by the improved transport links such as the widening of Theobalds Road (including the electric tramway system in 1906) and in 1900 the appearance of the Central Line and in 1906 the Piccadilly Line. The opening up of transport infrastructure meant that workers could travel to homes further away from the city centre and have personal gardens, allowing the general public to use the gardens in such squares as Red Lion Square. This Ordnance Survey map from 1914 illustrates both the parallel lines of the tram system on Theobalds Road and also the garden layout in the Square, presumably from 1885.

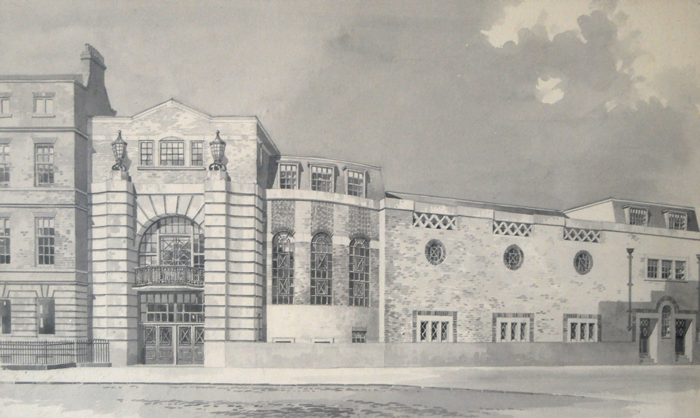

The first half of the Twentieth Century saw several unique building construction projects on the Square. In 1925, Summit House was built on the site of No. 12 Red Lion Square for the Austin Reed Company. The Austin Reed menswear company was founded in 1900 and by the 1920s had a flagship store on London’s Regent Street. The company commissioned the architectural practice of Westwood & Emberton to design a London headquarters for the company.

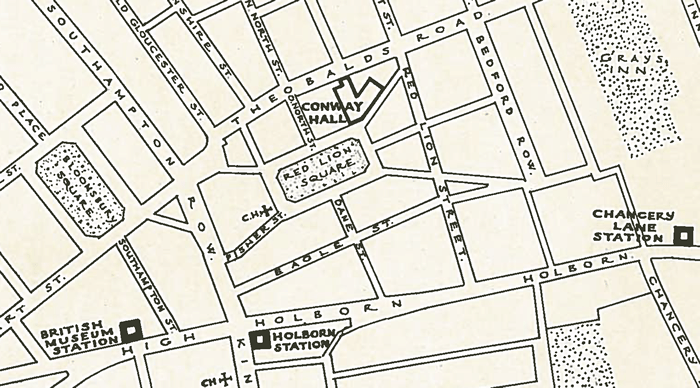

In 1927, the South Place Ethical Society, now the Conway Hall Ethical Society, purchased the plot of 25 Red Lion Square and Numbers 14 to 20 Lambs Conduit Passage that both used to form part of the Strictland Estate and upon which used to stand a school.

Following a successful appeal fund from its members, Conway Hall Ethical Society raised enough money to realise Frederick Herbert Mansford’s architectural vision for Conway Hall.

In 1938, Hanway House, named one presumes after Jonas Hanway, was built upon 27 – 31 Red Lion Square according to Edmund J. Thring’s design and became a regional office for the Ministry of Labour.

Progress and fortunes seemed in full swing with new construction projects and transport infrastructure giving a different shape to the Square and its immediate surroundings. However, everything for the Square was about to change.

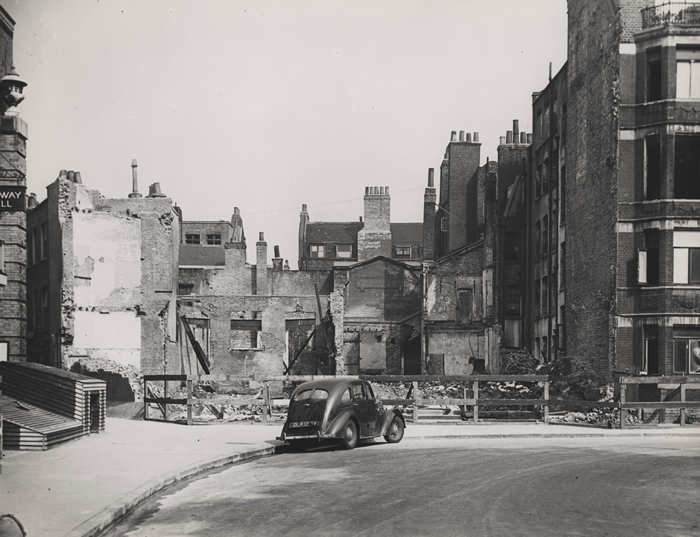

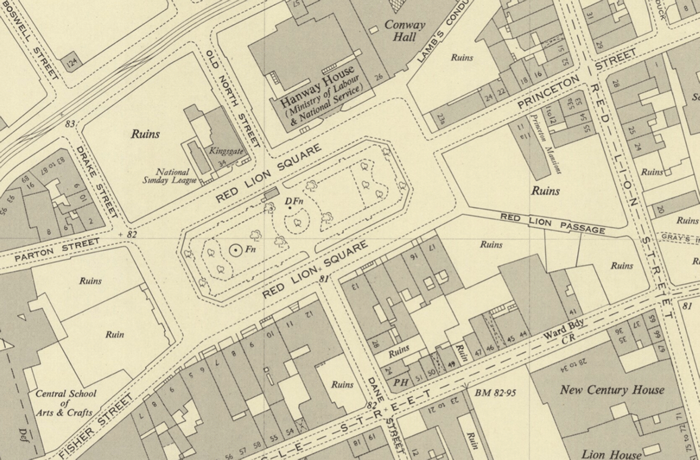

Eighteen months after the start of World War II, Red Lion Square was bombed during the Blitz. On Wednesday, 17th April 1941, a parachute mine destroyed St John the Evangelist church. Over 1000 people died that night across London.

Then, on their last major London raids on 10th and 11th May 1941, the Luftwaffe once more bombed Red Lion Square. This time No. 23 and 24 were obliterated ending the Red Lion Square address for the Sheriff of Middlesex and later Deputy Sheriff of London. An unexploded bomb also crashed through the Main Hall roof of Conway Hall.

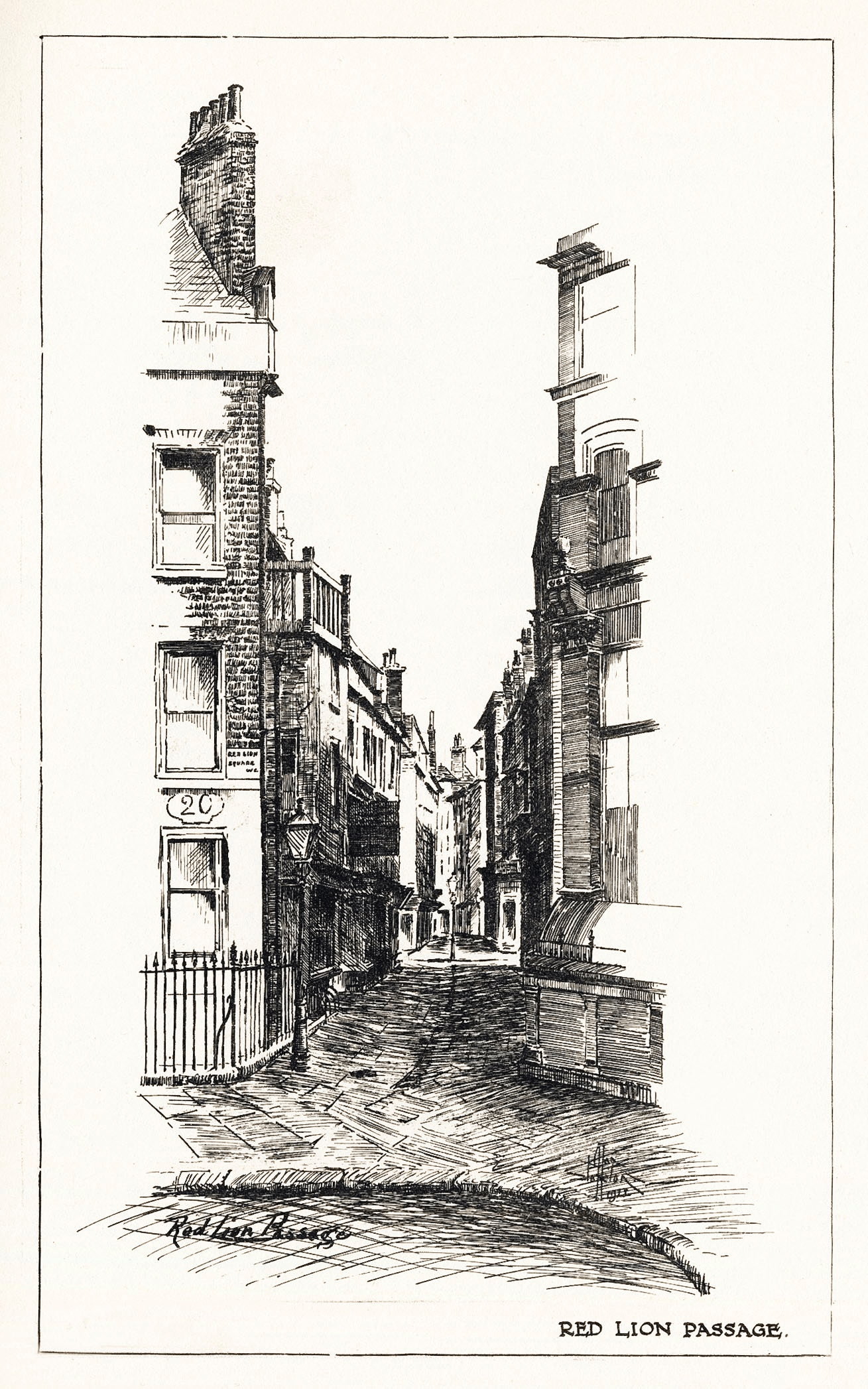

On the same night, another bomb exploded in Red Lion Passage destroying everything down the passage and also Nos. 18, 19, 20, and 21 Red Lion Square – the whole south-eastern corner. The passage used to be the province of second-hand book-shops as shown in the artist’s impression below:

The Blitz had eviscerated half of the buildings on the Square – Nos. 35, 36, 37 and 38 had also been decimated. The Square was forever changed on that May night in 1941.

As London woke up, or more likely dared to venture out after a sleepless night, members of South Place Ethical Society were arriving for their regular Sunday meeting at Conway Hall. Their scheduled speaker for that morning, Dr J. E. M. Joad had this to say:

“My first thought as l approached Red Lion Square this morning was “My God! it’s gone…” And then to my immense gratification I saw that although our next door neighbours had gone, Conway Hall remained. Inevitably we are few this morning and I think the question might be raised whether we should hold a meeting and go through the forms or our service at all. We judged it right to do so (cheers)… It is our tradition to meet every Sunday morning, and in the words of propaganda it would be a victory for Hitler if we stopped doing so.”

In the 1950s, rebuilding started and Red Lion Square gained new apartments blocks in the two bombed out areas on the east side, whilst Red Lion Passage was lost to memory.

I was wondering if you have any information regarding 19 Red Lion Square in 1865, I am researching one of my relatives John Pashley who was a picture frame maker previously of 3 black lion yard in 1865. The information I have leads him to this address but not if he was the owner of employed by someone else. I would be grateful for any information as have drawn a blank.

I have a coloured sketch of the bombed St. John’s red lion square any one have ant information. About this

Hello

Hanway house was designed by Trehearne & Norman, Preston & Co.; Edmund Thring produced the drawing working on their instructions, but was not the architect. You can see this at this link:

https://www.skinnerinc.com/auctions/3199T/lots/1077

I live on Princeton street (20/24). The small block is called Omnium court. The back of our block backs onto Lambs Conduit Passage. I would love any info to what might have been there before it was built in 1977

In Geoffrey Grigson’s autobiography, The Crest on the Silver (1950) is a wonderfully evocative description of Red Lion Passage in the early 1930s: ” The smell of Red Lion Passage in August, or even in December, was one of incomparable nastiness recalling Chadwick’s report of the London graveyards, effluvia of which would bring quick death to a canary hung out side in the cage; but I grew even to like the smell for the things which were to be found in the decayed shops of the Passage, a brown skull ( which I was not allowed to keep…)or an Ivory Coast carving, or a drawing by James Ward scrawled over with shorthand and boldly signed J.W. R.A. price sixpence…”