As the Eighteenth Century continued, Professor Theo Barker remarks that the Square “grew less fashionable” with some of the upper echelons of society moving away. For example, Sir Bysshe Shelley eventually moved away, and even built Castle Goring in Sussex, after living in the Square in 1753 where his wife gave birth to their son Timothy. (Timothy being the father of Percy Bysshe Shelley). The Square, it seemed, was becoming rather dour with the obelisk, iron fence and watch houses giving a “gloomy look” and, according to Barker, a visitor in 1771 compared the latter to “four family vaults and the obelisk to ‘the sad monument of a disconsolate widow for the loss of her first husband’.”

At some point, the following bizarre inscription was added to the monument “Obtusum obtusiores ingenii monumentum. Quid me respices, viator. Vade.” This translates as “A foolish monument to a more foolish deception. Why are you looking at me, traveller? Go away.” This suggests that the secret of the obelisk had been leaked, and royalists had attempted to denigrate the sanctity of this epitaph of republicanism. However, in August 1790, the Gentleman’s Magazine reported that the “monument” had been recently removed along with the “stone watch-houses at the four corners of the enclosure [Red Lion Square Gardens].”

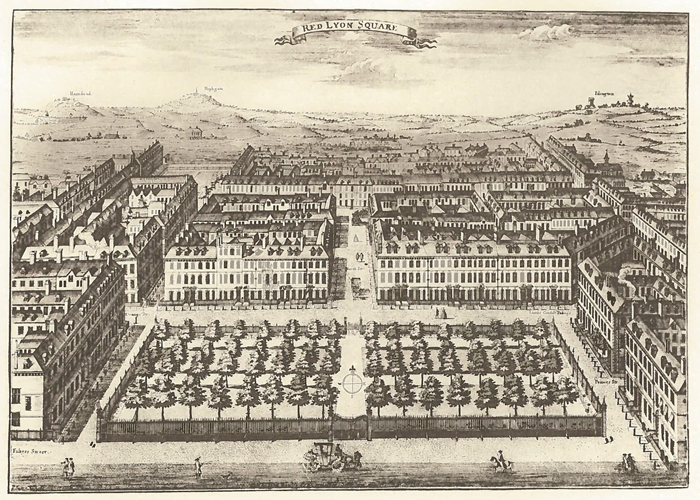

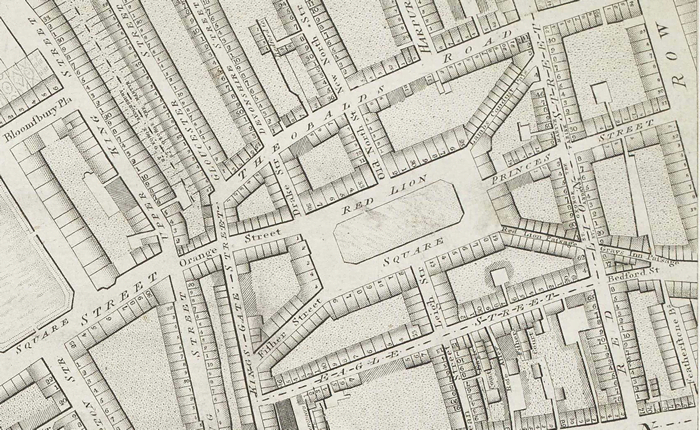

Sutton Nicholls, draughtsman and engraver, represented many of the squares in London for various surveys, such as John Bowles Prospects of the Most Noted Buildings in and about London (1724), London Described (1731) and the 1754 sixth edition of John Stow’s Survey of London. Red Lion Square is typical of Nicholls’ bird’s eye panoramic style and shows the watch houses but not the elusive obelisk. Hampstead, Highgate and Islington are shown on the horizon further north. A different perspective, by Richard Horwood, drawn up between 1792 and 1799 in his monumental survey of the whole of built-up London, offers no clarification as to the details of the Square’s accoutrements, but it does identify, as the assurance purpose of the enterprise demanded, a plan of the respective buildings surrounding the Square, complete with respective numbers.

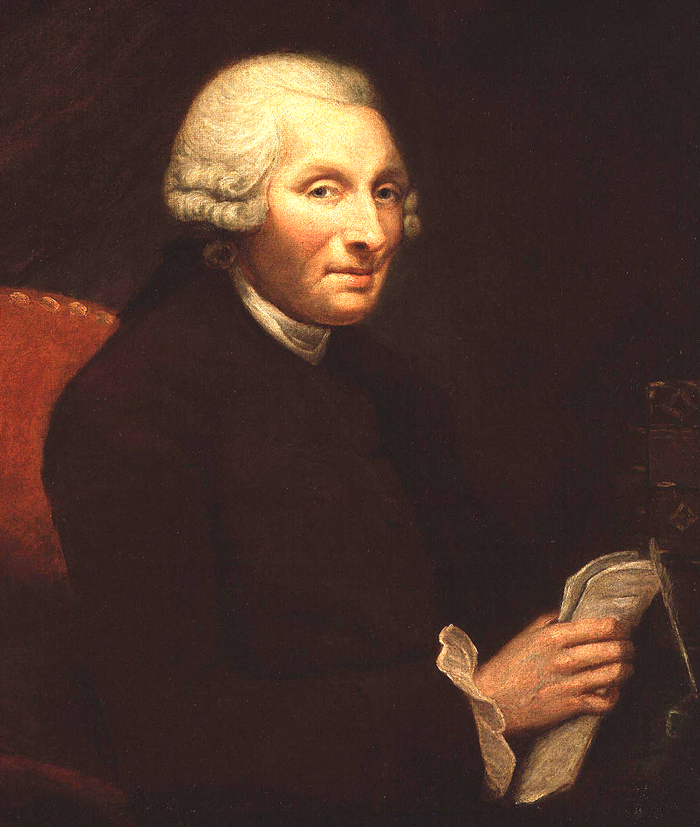

At No. 23 Red Lion Square, midway between Lamb’s Conduit Passage and Princes Street, Jonas Hanway, philanthropist and traveller, lived until his death in 1786 when he was given a public funeral, according to Edwin Beresford Chancellor’s, 1907 edition of The History of the Squares of London. The funeral, one is given to presume was due to his “amelioration of the lot of poor children” as opposed to the other recorded detail of his life, “his being the first man to habitually carry an umbrella in the streets of London.” In the late 1930s Hanway House was built at 27 – 31 Red Lion Square in his memory.

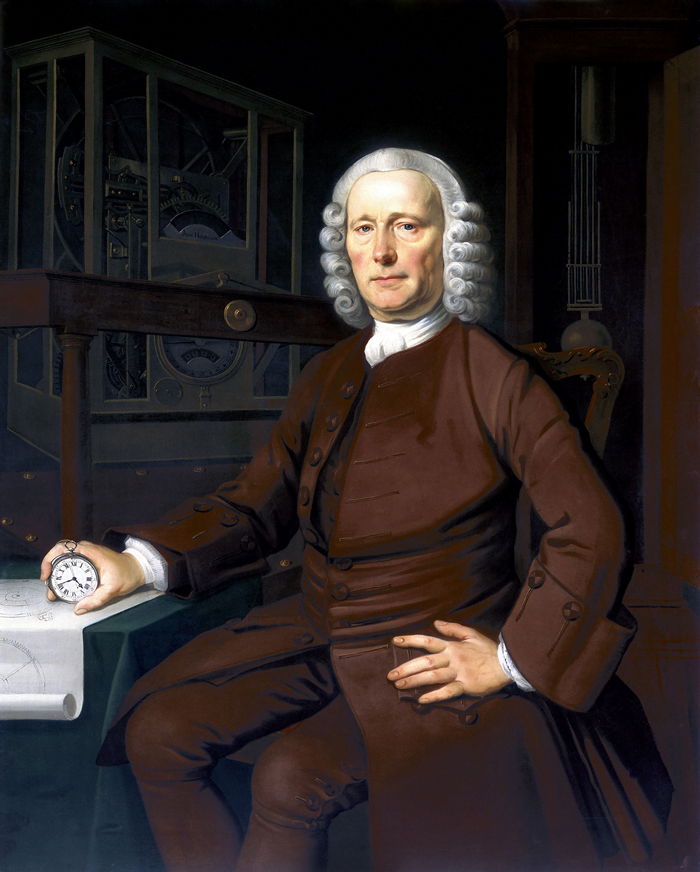

On his eighty-third birthday, in 1776, John Harrison died in 12 Red Lion Square, or just round the corner in Leigh (or Lee) Street, now Dane Street. Over the course of sixty years Harrison built clocks and is remembered in history as the man who solved the problem of longitude. Harrison’s “Sea watch” know as “H4” enabled Captain James Cook to navigate on his second and third voyages. Harrison’s marine chronometer revolutionised navigation and greatly increased the safety of long-distance sea travel.

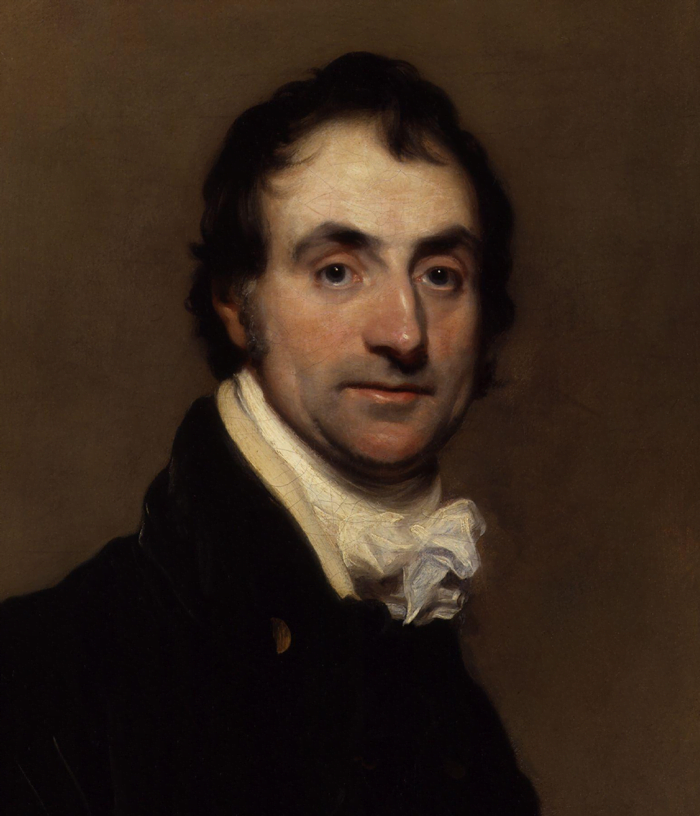

Around the time of his marriage, in 1795, the historian Sharon Turner moved to No. 13 Red Lion Square and researched extensively at the British Museum to write his History of the Anglo-Saxons in four volumes.

By 1822, however, No. 13 was the Headquarters of the Mendicity Society, According to the 1850 edition of the Hand-book of London: Past and Present, by Peter Cunningham, “The society gives meals and money, supplies mill and other work to applicants, investigates begging-letter cases, and apprehends vagrants and impostors. Each meal consists of ten ounces of bread, and one pint of good soup, or a quarter of a pound of cheese”. Cunningham also records that “the affairs of the Society are administered by a Board of forty-eight managers”.

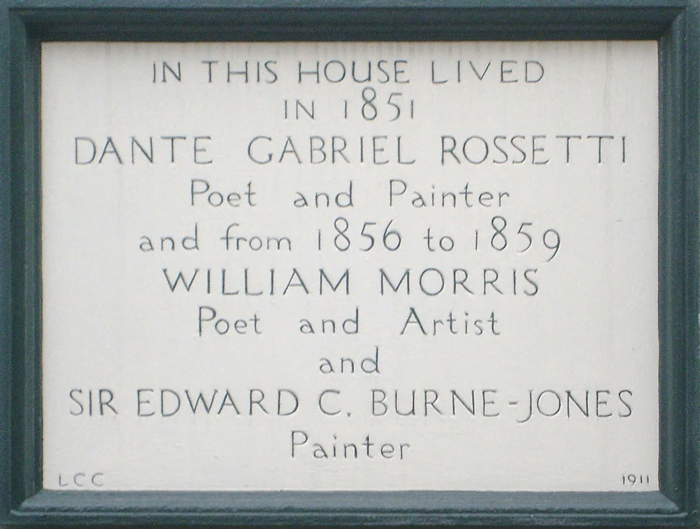

Perhaps the most famous residents of Red Lion Square are those recorded by their plaque at No. 17. Chancellor was particularly enamoured by this piece of history: “not only did Rossetti and Walter Henry [Howell] Deverell once live here; but later Burne-Jones and William Morris came to reside in the same house; such a constellation, indeed, as can be matched by no other residence, it is probable, in all London.”

In 1848, seven artists and critics, in the main recent graduates from the Royal Academy, formed the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB). On Dante Gabriel Rosetti’s behalf, Thomas Woolner, the only sculptor in PRB, enquired about lodgings at No. 17 on the first floor. The three rooms were available at 20 shillings per week (roughly £70 as at 2017). There was a stipulation from the landlord however, when he understood that artists were interested in his rooms: models were to be kept under “gentlemanly restraint” because in his opinion “some artists sacrifice the dignity of art to the baseness of passion”. Stipulations considered, Rossetti and Deverell took up residency in 1851 and lived there for a brief spell of six months.

In 1856, Rossetti suggested to Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris, two of his fellow Mediaevalists and Arthurian Romanticists within the widening circle of the PRB, that they take his former lodgings at No. 17. For three years the two artists resided in Red Lion Square. During this time their maidservant, Mrs Mary Nicholson, became known as “Red Lion Mary”, and by all accounts put up with the bizarre and sometimes demanding behaviour of the two and their friends with great humour and loyalty.

In 1916, Max Beerbohm created a series of drawings and watercolours entitled Rossetti and His Friends and illustrated how he imagined William Morris, ‘Topsy’, and Edward, ‘Ned,’ Burne-Jones amidst their own medieval themed designed furniture, in an otherwise sparsely decorated space.

After leaving the Square in 1859, William Morris returned in 1861, to No. 8 Red Lion Square, with some of the other PRB members to establish the headquarters of what would eventually be known as Morris and Co.

Pingback:Vic Keegan's Lost London 165: Nicholas Barbon and the brick-throwing lawyers of Red Lion Square - OnLondon